Making your own RISC-V CPU is a terrible idea. I have said that many times before. There are already a million RISC-V cores out there to choose from, so making another one makes no sense at all. It's kind of the same thing with UARTs. There are probably as many UART cores written as there are people using one. In my opinion, it's much more important to learn how to reuse and contribute to existing cores than making your own. I remember musing at ORConf one year that I was probably one of the only people in the room who hadn't built their own UART or RISC-V core. Although... I actually made a UART a couple of years ago. But only because I had to see if I could make a UART that fit inside a tweet. And you know what's worse? I actually made a RISC-V CPU as well. In fact, the world's smallest RISC-V CPU. But I never intended to. So how did it all happen? Well, on this day five years ago, I made the first commit to the CPU that would eventually be SERV. But to see how it really started we need to go back in time one more month to September 21 2018, just before teatime.

In Gdansk, Poland, we were organizing ORConf. As usual there were a lot of great presentations covering a wide array of topics. One of those was a lightning talk by Michael Gielda of Antmicro. RISC-V Foundation, as it was known by then before the formation of RISC-V International, together with Google, Antmicro and MicroSemi had decided to organize a contest. The idea was to let contestants build either the fastest or the smallest RISC-V CPU for a given FPGA board. It had to pass a suite of compliance tests and it had to correctly execute some example programs, including running the Zephyr real-time operating system. The deadline was November 26, meaning just over two months to put together a core together with at least a minimal set of peripheral controllers to create a small SoC, figure out how to run the compliance test suite and port Zephyr to the SoC.

I remember thinking that this sounded like a lot of fun, but quickly realized there was no way I would ever find the time to do such a thing, so I basically forgot about it for my own part.

About a month after that, I was at home doing the dishes when I started idly thinking about that processor contest. In particular, I started thinking, what if you do an operation on two 32-bit vectors, but only process one bit each cycle? Then you could theoretically reuse the same circuitry 32 times instead of having 32 separate copies of basically the same thing.

At this point I had no idea that was called a bit-serial algorithm and was an idea people had already come up with and that was quite widely used in CPUs in the 70s.

So after finishing up the dishes I had to try out this idea on a piece of paper. It obviously worked for boolean operations such as and, or, xor, but it turned out also to work for additions (and by extension subtractions, which can be described as additions). To convince myself that it actually did work, I made some simple Verilog and ran it through a simulator. And when that worked I got curious about what operations that a RISC-V CPU had to implement so I opened the base specification for the first time and started reading. I was so amazed by the simplicity and how well thought-out the whole thing seemed to be. Having read at least a few similar documents before, this really stood out as a piece of art. And also, it got me thinking that maybe, just maybe, it wouldn't be impossible to actually do a CPU. I could at least give it a try and see. Just for fun, you know.

So on October 23 2018 I pushed a first commit to the newly created SERV repo and suddenly I found myself making a CPU. By this time, half the contest time had already passed which was not an ideal situation, but I did it mostly for fun so it didn't matter too much. The evenings and weekends during the following month was spent doing Karnaugh maps and schematics on

paper while putting the kids to bed and then turning it into verilog.

And finally, a few hours before the deadline on November 26, I got the Dining Philosophers Zephyr application running, which was one of the requirements, and that was that. Most of the people involved in the contest were exchanging tips, experiences and metrics on a forum. From the discussions there I knew that SERV had no chance of winning since it wasn't the smallest and definitely not fastest, but it had been a fun experience and I got a new appreciation of the RISC-V ISA, so I was happy regardless.

About a week later, I woke up to a lot of congratulations on social media. The first RISC-V Summit was ongoing on the other side of the planet and it turned out

I had won an award for SERV after all. Not for being the smallest, and definitely

not for being the fastest, but for being the most creative solution:)

|

SERV becomes The award-winning SERV

|

As the code had been written to meet a one-month deadline, the implementation

was rushed, to say the least. But during the development I had gotten plenty of ideas for further improvements. So free from any time pressure, I continued working at my own pace. During the kids ballet lessons I drew schematics and

instead of bedtime reading I made more Karnaugh maps and SERV steadily

became smaller and smaller.

In March 2019 I submitted an proposal to speak at the RISC-V workshop during the Week of Open Source Hardware (WOSH) in Zürich that summer with the first ever presentation of SERV called

Bit by bit: How to fit 8 RISC-V cores in a $38 FPGA board. The board in question was the TinyFPGA BX, in case someone is curious.

The presentation was accepted, but it turned out to be a terrible name for a talk. You see, before the end of March I had made some changes to fit 10 cores inside that FPGA. After arriving in Zürich I had that number further increased to 14, and on the day of the presentation I had managed to fit 16 cores into that FPGA, so I had to make some last minute adjustments to the slides. The talk went fine but not great. However, for some unknown reason it has managed to become the second most viewed video on the RISC-V YouTube channel. I guess this is the closest I'll ever be to become a YouTuber.

|

Note to self - never put performance numbers in a presentation title

|

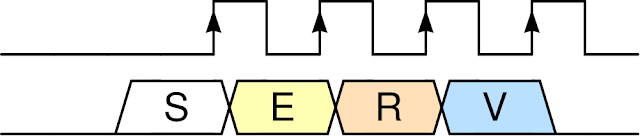

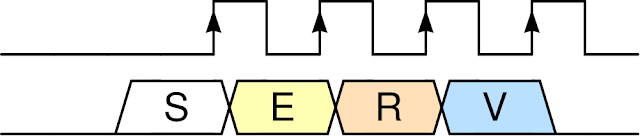

Another important milestone that happened just before heading to Zürich was that SERV got its logo.

|

Designed using WaveDrom, the amazing timing diagram (and logo designer) tool. Here's the source for the logo https://wavedrom.com/editor.html?%7Bsignal%3A%5B%7Bwave%3A%270.P...%27%7D%2C%7Bwave%3A%27023450%27%2Cdata%3A%27S%20E%20R%20V%27%7D%5D%7D

|

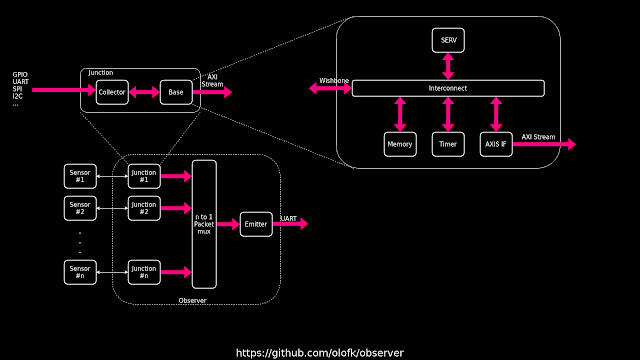

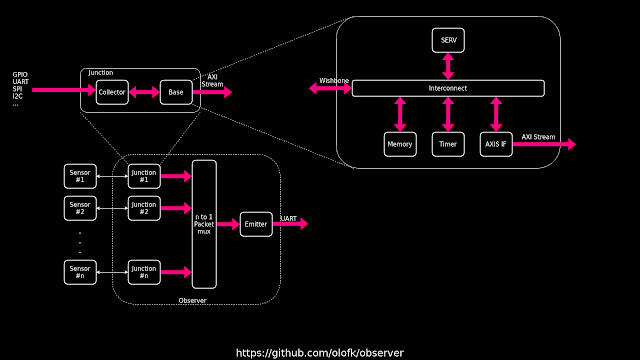

In September the same year I learned about another contest, the European FPGA Developer Contest, by Arrow Electronics. In a fit of hubris, I entered that contest too, thinking I had such a great idea that there was a serious chance of winning. The idea was a programmable heterogeneous sensor fusion platform in which you had an FPGA that was connected to a bunch of sensors. Data was collected from each of the sensors and combined into a message stream. The novelty here was to dedicate a SERV core to each sensor. That meant that each CPU could handle the parts of sensor communication that was easiest to do in software, like configuring and handling spi/i2c transactions, while using FPGA fabric to do custom protocols and heavy processing. I called the project Observer and released it on Github

|

I felt very clever about the naming scheme of Observer. The sensor data came in through a "collector" and then the "base" controlled the data flow. Together those formed a "junction". All data streams then merged and was then sent off-chip through a "common emitter".

|

I still think it's not a half-bad idea, but at the same time there isn't a super clear use-case for it and it would require a lot more work than I was willing to put in to get it really usable. Speaking of work, I wanted to have a nice logo for the project, so I asked my very talented fiancée to draw one for me. She didn't have time so instead I made the crappiest logo I could come up with in ten minutes, proudly showed it to her saying that it had been released on the internet. The plan worked perfectly. Upon seeing the logo, she felt so embarrassed for me that I soon had a stunningly beautiful logo replacing the old one. The moral of the story: If you do something bad enough, someone will eventually be unable to resist improving it.

|

I have done many ugly things in my life, but the original Observer logo still hurts to look at

|

In the end I didn't win anything, although I did get to keep the very nice cyc1000 FPGA board. I believe some AI something something won, but I'm not sure actually. The other projects were never released anywhere to my knowledge and the whole thing felt slightly shady. And after that, Observer sank down on my list of priorities and has been laying dormant, but it did have one everlasting legacy that became its own, much more well-known project.

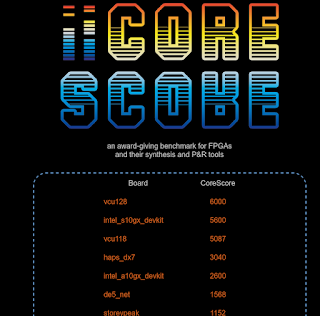

While working on Observer, I used the on-board sensors to have some data sources to combine. There was a button, an accelerometer and...well, that was it. It felt a bit silly to have a sensor fusion system with only two sensors though. The proper thing to do here would had been to solder on a couple of more sensors, but I chose a less work-intensive way, and instead added some SERV cores that just wrote random strings without ever being connected to any sensors. (Remember, kids! Always cheat if you have the option). After adding a couple of more SERV cores generating fake sensor data, I realized that there was still a lot of room left in the FPGA. So I added a couple of more cores and there was still room left. By now I had completely abandoned all pretentions of creating a useful system and just wanted to see how many SERV cores I could stuff into the FPGA. Then, of course, I got curious to see how many cores I could stuff into other FPGAs that I had at hand. Somewhere around this point I realized that this had now become its own project, with the sole intention of finding a metric for how large an FPGA is, by measuring the number of SERV cores they could fit.

For the first three minutes of existence, the project was called ServMark until I settled in the much catchier CoreScore. I then went to my fiancée again, got an amazing logo and started checking the scores for other boards at my disposal.A couple of days later I registered corescore.store, got some JavaScript help to create a dynamic high score list and started inviting other people to submit their CoreScores. At the time of writing, there are now more than 40 different FPGA boards on the list, with the top entry hitting 10000 cores.

|

CoreScore with its beautiful logo and the top five entries at the time of writing. Check out the site for the latest results.

|

I believe 10000 cores is the highest number of RISC-V cores anyone has put in a chip, at least at the time of writing. Not that they are doing anything useful, but still, I sincerely believe it has a useful purpose. First of all, it gives a rough metric of the relative size between different FPGAs, which normally tends to be an apples-to-oranges comparison thanks to different LUT sizes and available memory blocks. It's not perfect, but provides some guidance, especially to those new to FPGAs. It's also a way to compare the efficiency of FPGA toolchains. With open source alternatives popping up for more devices, it can be interesting to see how well they compare to their proprietary alternatives. For my own part, the prospect of getting higher scores has been a good motivation for further optimizations of SERV, so it has been helpful in that regard too. The rest of 2019 I was working on and off continuing to bring down the size of the core, and by the end of the year there was no doubt that it had surpassed all other RISC-V cores in terms of size, making it The award-winning SERV, the world's smallest RISC-V CPU.

As we rolled into 2020, there was something in the air that had a big impact on most people's lives, and gathering in large groups at conferences was just out of option. What happened instead was that people took their slideshows into video calls instead at online conferences. I went to one of those in early 2020 and I absolutely hated it. I could see no reason for watching decapitated heads - most of them struggling to handle the lack of audience feedback - reciting slides decks aloud, when I could just as well just read the slides myself or watch a recording where I could skip the boring parts or listen again if something wasn't clear.

Then, in the spring, I was asked if I could present at one of these virtual conferences. With all the latest advances of SERV I really wanted to present that, so I accepted, but also started thinking if there was a better way to use the new medium than the horrible slide decks I had been subjected to. I decided early to prerecord something. It didn't make sense for the audience to hear me mumbling and losing the thread, when I could just as well edit it to something more coherent beforehand and save everyone's time. I also realized that since everyone would watch it on a computer screen, and not on a projected screen in a badly lit room, I could afford having much finer details in the pictures. And most of all, I could have animations. And sound! So, stylistically inspired by a 1981 video on sorting algorithms we had been forced to watch in school and educational animations from my childhood, I equpped myself with a Korg Monotron for sound effects and a Python animation library to work on creating a fully immersive multimedia edutainment experience about SERV.

Creating a video like this also meant that it could not only be used for that particular online event, but could also be viewed anytime by people who wanted to get an introduction to SERV.

On April 29, the resulting video was aired during the 1st Virtual Munich RISC-V Meetup, about 24 minutes in. And for those who prefer just to watch the SERV video without the rest of the talks, it is also available here.

Doing a video was a lot of fun, but there is another common way to make people aware of your work - writing papers. It so happened that my friends at ETH Zürich had just released a paper called Manticore: A 4096-core RISC-V Chiplet Architecture for Ultra-efficient Floating-point Computing. Now, 4096 cores with area-efficient floating point support is of course impressive, but I thought I could do better in at least one metric, the sheer number of cores. So over 2 days in May 2020 (~15 hours of struggling with Latex and maybe an hour actually writing the thing) I put together the first paper on SERV, Plenticore: A 4097-core RISC-V SoClet Architecture for Ultra-inefficient Floating-point Computing. For some reason it was never accepted into any conferences and has been cited approximately zero times, so I guess I will have to wait a bit longer for my academic career to take off.

At this point, SERV had been implemented in plenty of FPGA projects by myself and other people, but to my knowledge hadn't been taped out. But 2020 also brought the OpenMPW program with free tapeouts for open source projects. Wanting to both add support for the OpenLANE open source ASIC toolchain in Edalize and getting some real SERV chips, I applied for funding through NLNet Foundation to add Edalize support for OpenLANE and use that to make a small SERV-based SoC. Both objectives were successfully accomplished and thus the Subservient SoC was born, which is a minimal SoC, just like Servant, but more suitable for ASIC implementations.

Over the year SERV continued to see more code commits titled optimize this or simplify that, and in addition to working on the core itself, I added documentation and other people got it running on more FPGA boards

Having so much fun making the first SERV video, as well as one on Edalize (that actually won an award!), I decided to make another one for the 2021 virtual event RISC-V Forum : Embedded Technologies. In that case it was even better to have it prerecorded since it was broadcast around 4 am my time and I don't think I would have given a very good talk at that time of the day. This time I went more for day time TV aestethics and I think it turned out pretty nice.

This video was also the debut of the first major external contribution, with the (optional!) support for the M extension contributed as a Google Summer of Code project.

At this time, I was still trying out some further optimizations, but it started to get really, really hard to make further improvements to the size. I could spend a week working on an idea for an optimization only to find out it didn't improve anything at all, or even made SERV slightly larger. Generally, only 1 out 10 ideas for optimizations yielded any positive results. There are still some ideas left to try out but they require a bit more time and effort than I have been able to spend. I will mention a few of these later on in the future outlook.

|

The amount of effort trying to further minimize SERV is pretty much the inverse of the resource usage chart

|

So the last years have focused more on features. Early in 2022, I added support for ViDBo, the Virtual Development Board protocol that allows interacting with a simulation of the Servant SoC through an interactive picture of an FPGA board presented in a web browser. It's a pretty fun way to try out SERV if you don't have a real FPGA board. The spring of 2022 also brought (optional!) support for the C extension thanks to another student that I mentored through the LFX Mentorship Program.

But no matter how small or featureful SERV is, what matters in the end is where it is actually used. As with most of my (and others) open source projects, you typically have no idea about most of the places where it is implemented. People only tend to reach out when they need support (which I'm happy to offer for SERV and my other open source projects, and already do for several clients) but I have learned about some use-cases over the years, such as USB-to-serial converters, DDR2 initialization, GPS synchronization for RADAR and power management. Two of my favorite applications is a cranial implant ASIC and a research project that has taped it out on the PragmatIC FlexIC process, likely making SERV the first RISC-V CPU to be taped out on plastic film. In general, the small size, and hence the simplicity has made it a an attractive choice for taping out on novel processes where yield is not yet maximized.

And that pretty much sums up the first five years of SERV. What about the next five years? There are a number of half-finished ideas that I would like to finish up as well a couple of things that I haven't even started. Looking outside the core, I have more or less finished a new framework for CoreScore that will both allow more cores to fit in the same area as well as making routing easier and thereby faster for the P&R tools. As a point of reference, it apparently took around 48 hours to do P&R on the 10000 cores that occupies the number one spot on the list right now. And I would of course like to see both CoreScore and Servant running on more FPGA boards, and that's where you, my dear readers, can help out by making sure it runs on your board and submit a patch to get it added.

For the core itself, more ISA extensions would be nice. Most of them, like floating point support, doesn't make very much sense, but why not. It would be very cool to run Linux on SERV, and for that we probably need to at least implement the atomic instructions and some more pieces of the privilege spec. More interrupt sources and a debug interface has been requested as well, which makes sense. I also have an almost completed project that uses some nifty math to calculate the smallest decode unit, given some constraints. The plan is to do a proper write-up about that and perhaps even put out another paper.

But the thing that most people seem excited about is having 2-, 4- and maybe 8-bit versions of SERV. Those would be slightly larger, but also almost 2, 4 or 8 times faster than SERV is today. Preliminary results have shown that the size of wider versions grow less than one might think. There is actually a big reveal coming up in this department soon. If you read this a couple of weeks after I write this, you will already know what it is, but I'm keeping it a secret for now :)

So, all in all, I'm pretty damn proud of SERV and it has been a lot of fun working on it. It has also managed to attract commercial interest from some of the larger players in the RISC-V space while still remaining very much a passion project for which I can curl up on the couch with a cup of coffee on a Sunday afternoon and think about some optimizations, draw some schematics or Karnaugh maps just like normal people do crosswords.

Happy fifth Birthday, SERV. As a proud parent, I'm amazed to see how small you have become since you were a baby.